Table Of Content

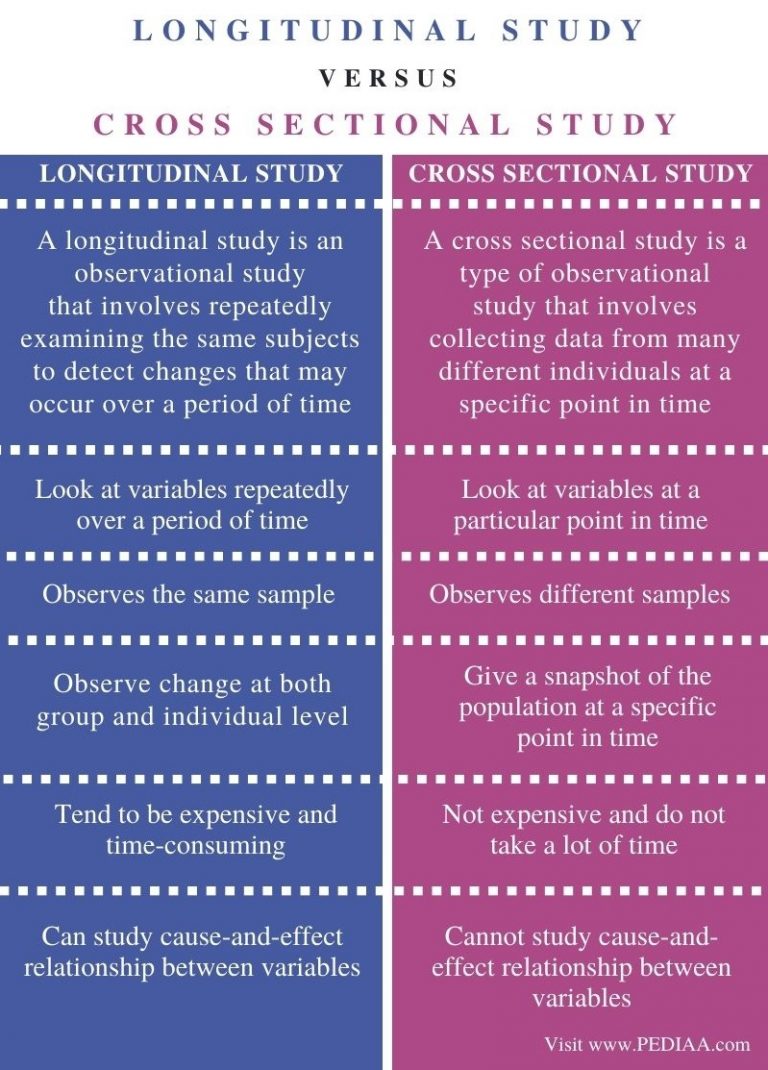

Notably, this stabilizing effect exists independently of the differences in memory and mental aggregation that are described below. Cross-sectional research is easier to conduct than longitudinal research, but it often estimates the wrong parameters. Interestingly, researchers typically overemphasize/talk too much about the first fact (ease of cross-sectional research), and underemphasize/talk too little about the latter fact (that cross-sectional studies estimate the wrong thing). Within-subjects designs, in which people are repeatedly measured, may be subdivided into non-longitudinal and longitudinal types.

Recurring Surveys

Conducting a longitudinal study with surveys is straightforward and applicable to almost any discipline. Consider a study conducted to understand the similarities or differences between identical twins who are brought up together versus identical twins who were not. The study observes several variables, but the constant is that all the participants have identical twins. Many medical studies are longitudinal; researchers note and collect data from the same subjects over what can be many years.

Retest effects

Discontinuous change is the second set of functional form with which one could theoretically describe the change in one’s substantive focal variables. For example, according to the stage theory (Wang et al., 2011), retirement may be such a precipitous event, because it can create an immediate “honeymoon effect” on retirees, dramatically increasing their energy-level and satisfaction with life as they pursue new activities and roles. Indeed, there is some evidence that contingent incentives are effective in longitudinal designs (Castiglioni, Pforr, & Krieger, 2008). Although this strategy is consistent with theory and evidence just discussed, it has yet to be tested explicitly. The particular choice of item type (i.e., immediate vs. aggregated experiences) that will be of interest to a researcher designing a longitudinal study should of course be determined by the nature of the research question.

Goals of Longitudinal Data and Longitudinal Research

For example, it is possible to implement repeated surveys for a particular mobile operating system (OS; e.g., Apple’s iOS, Google’s Android OS), but unless a member of the research team is proficient in programming, there will be a non-negligible up-front cost for a software engineer (Uy, Foo, & Aguinis, 2010). Furthermore, as market share for smartphones is currently divided across multiple mobile OSs, a comprehensive approach will require software development for each OS that the sample might use. Moreover, they often leave to the imagination the implications of the theory on behavior.

These research studies can last as short as a week or as long as multiple years or even decades. Unlike cross-sectional studies that measure a moment in time, longitudinal studies last beyond a single moment, enabling researchers to discover cause-and-effect relationships between variables. In longitudinal studies, researchers do not manipulate any variables or interfere with the environment. Instead, they simply conduct observations on the same group of subjects over a period of time. Let’s assume, for example, that you conduct an employee engagement survey every year.

Examples of Longitudinal Surveys

Because cross-sectional studies are shorter and therefore cheaper to carry out, they can be used to discover correlations that can then be investigated in a longitudinal study. Inaccuracies in the analysis of longitudinal research are rampant, and most commonly arise when repeated hypothesis testing is applied to the data, as it would for cross-sectional studies. This leads to an underutilisation of available data, an underestimation of variability, and an increased likelihood of type II statistical error (false negative) (8). Participants sometimes drop out of a study for any number of reasons, like moving away from the area, illness, or simply losing motivation.

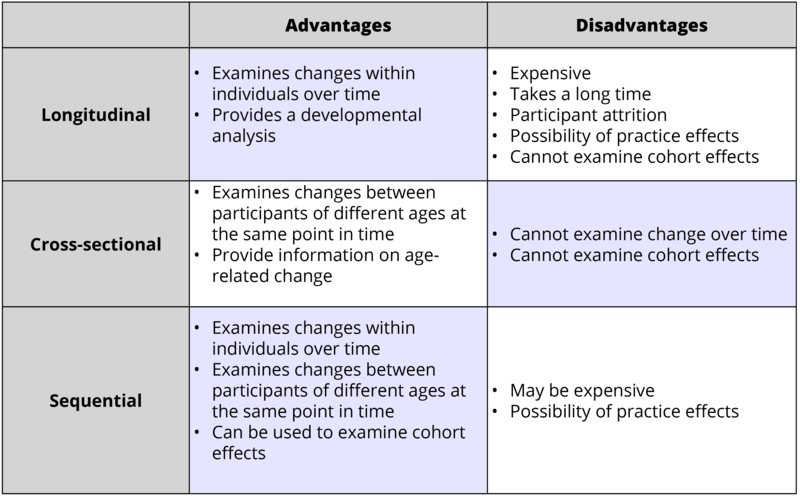

Advantages of Longitudinal Studies

Although process dynamics can (and do) occur at all levels of analysis, I am particularly excited by the prospect of linking them across at least adjacent levels. Spline regression is used to model a continuous variable that changes its trajectory at a particular time point (see Marsh & Cormier, 2001 for technical details). For example, newcomers’ satisfaction with coworkers might increase steadily immediately after they enter the organization.

Now the researchers will give a log to each participant to keep track of how much and how frequently they play and how much time they spend playing video games. During this time, the researcher can compare video game-playing behaviors with violent tendencies. Over many years, researchers can see both sets of twins as they experience life without intervention. Because the participants share the same genes, it is assumed that any differences are due to environmental analysis, but only an attentive study can conclude those assumptions. In cohort studies, researchers merely observe participants without intervention, unlike clinical trials in which participants undergo tests. When using this method, a longitudinal survey can pay off with actionable insights when you have the time to engage in a long-term research project.

Indeed, one way to know if one is measuring a dynamic variable is if one observes a simplex pattern among inter-correlations of the variable with itself over time. In a simplex pattern, observations of the variable are more highly correlated when they are measured closer in time (e.g., Time 1 observations correlate more highly with Time 2 than Time 3). Of course, this pattern can also occur if its proximal causes (rather than itself) is a dynamic variable.

On the methodology level I think research simulations (i.e., virtual worlds) will increase in importance. They offer a great deal of control and the ability to measure many variables continuously or frequently. On the analysis level I anticipate an increased use of Bayesian and Hierarchical Bayesian analysis, particularly to assess computational model fits (Kruschke, 2010; Rouder, & Lu, 2005; Wagenmakers, 2007). Perhaps the most obvious difference across this continuum of abstraction is that different degrees of aggregation are captured.

It is common to see authors attribute their high confidence in their causal inferences to the longitudinal design they use. It is also common to see authors attribute greater confidence in their measurement because of using a longitudinal design. Less common, but with increasing frequency, authors claim to be examining the role of time in their theoretical models via the use of longitudinal designs. These different assumptions by authors illustrate the need for clarifying when specific attributions about longitudinal research are appropriate. Hence, a discussion of the essence of longitudinal research and what it provides is in order.

What Is a Longitudinal Study? - Verywell Mind

What Is a Longitudinal Study?.

Posted: Sat, 02 Dec 2023 08:00:00 GMT [source]

Unfortunately, three observations of each variable is only a slight improvement because it might be a difficult thing to get enough variance in changing attitudes and changing intentions with just three waves to find anything significant. Indeed, the researcher might have better luck looking at actual retirement, which as mentioned, only needs one observation. Still, two observations of job satisfaction are needed prior to the retirement to determine if changes in job satisfaction influence the probability of retirement. I predict that significant advances in various areas will be made in the near future through the appropriate application of mixture latent modeling approaches. These approaches combine different latent variable techniques such as latent growth modeling, latent class modeling, latent profile analysis, and latent transition analysis into a unified analytical model (Wang & Hanges, 2011).

However, Terman was a proponent of eugenics and has been accused of letting his own sexism, racism, and economic prejudice influence his study and of drawing major conclusions from weak evidence. For example, a recent study found new information on the original Terman sample, which indicated that men who skipped a grade as children went on to have higher incomes than those who didn't. If the final group no longer reflects the original representative sample, attrition can threaten the validity of the experiment. Validity refers to whether or not a test or experiment accurately measures what it claims to measure.